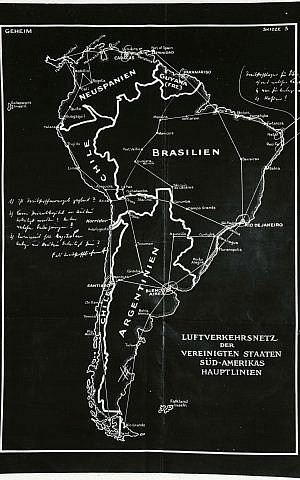

As much of Europe, Africa and Asia fell under the control of the Axis Powers in 1941, United States president Franklin Delano Roosevelt faced a chilling discovery — an alleged German map of postwar plans for South America, in which the continent’s nations would be replaced with four Nazi territories.

Soon obscured by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor that resulted in US entry into World War II, this document nevertheless indicates that Latin America played a more important role in the conflict than many think. It’s one of many revelations in a new book, “The Tango War: The Struggle for the Hearts, Minds and Riches of Latin America During World War II,” by journalist Mary Jo McConahay.

Those enlisted in the “struggle” of the book’s subtitle include leaders such as FDR and entertainers including Walt Disney, who traveled to the region to make films that would create a cinematic bridge between US and Latin American audiences. Disney’s first such film, “Saludos Amigos,” featuring Donald Duck, Goofy and a Brazilian parrot named Jose “Joe” Carioca, was released in the US 76 years ago this February.

McConahay also discusses the only Latin American unit to fight in Europe during the war — the 25,000 Brazilian “Smoking Cobras” who distinguished themselves in Italy in 1945, piercing the formidable Gothic Line and capturing thousands of prisoners.

There are uncomfortable moments in the story: the region’s underwhelming response to Jewish refugees during the Holocaust, including the doomed ship St. Louis; a secret US program that kidnapped ethnic Japanese and Germans in Latin America — including Jews — to exchange for Americans imprisoned by the Axis; and the Ratlines that helped Nazi war criminals escape to South America.

McConahay’s interest in the region was sparked by her late father, who served there with the US Navy and shared reminiscences. She became an award-winning journalist while covering Latin American wars. After writing two memoirs of her time there, McConahay decided to tackle the region’s role in WWII.

This precedent-setting project posed challenges.

“I could find no book in English that could talk about the whole arc of experience of WWII in Latin America,” McConahay said. “Are there some academic tomes? Yes, there are. But there’s nothing for the general reader — perhaps a reader who is not even particularly interested in Latin America but maybe in WWII. Or a reader who is interested in Latin America but not WWII. Or just the reader who wants a good read for an airplane ride.”

Regardless of motivation, readers might be in for some surprises about the vast, mainly Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking region that stretches from the Rio Grande to the southern tip of Argentina.

“I find that people are largely unaware of the importance of Latin America during the Second World War,” McConahay said.

At book publicity events, “I go into why Roosevelt was so concerned about Latin America over the possible fifth columns that could be among the populations there because of Fascism,” she said. The region was “so close to the hump of Africa, soon taken by the Reich,” she noted, and “an incredible mine of materials absolutely fundamental to the war.”

Evoking the book’s title, Axis and Allies shadowboxed across the region through strategies such as propaganda and espionage, with ordinary people caught in between.

Remembrances from such individuals illuminate the story. Being a reporter, McConahay said, “the first thing that comes to my mind” when she unearths information is “can I find any people who are still alive, one person who can give information about these incredible events?”

This was how she shared the impact of the St. Louis on a German Jewish refugee family in 1939.

Patriarch Ludwig Unger was decorated for fighting for the Kaiser in World War I. When his homeland turned against him with Hitler’s rise, he escaped to Guatemala through a family connection. Unger changed his first name to Luis and waited for his wife, Betty Unger, and her sister, Gusti Hansen, to arrive on the St. Louis, a luxury liner-turned-refugee ship bound for Havana.

There, most of the 900 passengers learned their visas were invalid because the Cuban official who approved them was deemed corrupt. The ship tried to reach the US but was pressured away by the Coast Guard. It returned to Europe, where hundreds of its passengers perished in the Holocaust — including Betty and Gusti, who both died at Sobibor.

“I know the grandson of one of [the sisters] personally,” McConahay explained. “I was able to tell the story in a lot of detail… taking the reader through the hope that was first there with folks coming to Latin America, and the crushing disappointment when it was taken away.”

The ship was “a metaphor, it seemed to me, for the point to which the cynicism and callousness of Latin Americans and of the US could reach,” McConahay said.

The book also shares the adversity faced by “native” Latin American Jews, whose presence dates to the time of Columbus and his six “converso” crewmen. Surviving the Inquisition, Sephardim — or, Spanish Jews — were later joined by coreligionists from Germany. In general, McConahay said, they coexisted peacefully with non-Jews before the war exposed anti-Semitism.

“It was really WWII that took the lid off and let it flower, you might say,” McConahay said. “There were many stories about Jews and their neighbors happy together, playing ball, and all of a sudden a Jewish neighbor watches a non-Jewish neighbor put on the green uniform of the local Fascist party.

“Anti-Semitism was all over Latin America… Even the Nazi Party was legal [in Latin America] to a certain point. Often, groups were homegrown. It led to preventing Jews from coming into Latin America. In many cases, Latin countries looked to US law as a model. US law at the time was about quotas,” she said.

In the book, she writes that 84,000 Jewish immigrants “managed to plea, cajole, or bribe their way into refuge in Latin America between 1933 and 1945, less than half the number admitted during the previous fifteen years.”

Some Latin American officials in Europe acted valiantly, including Jose Arturo Castellanos, an El Salvadoran consul general in Geneva, who saved an estimated 40,000 Jews from death camps; and Gilberto Bosques Saldivar, a Mexican consul general in Marseilles, who rescued tens of thousands of Jews before being captured by the Nazis and needing his government to arrange a prisoner exchange on behalf of “the Mexican Schindler.”

Latin American leaders played a complex role. McConahay describes Lazaro Cardenas, the Mexican president at the war’s outset, as wishing to sell oil to democratic countries but compelled to sell to the Reich instead. His country was, however, a lone voice against the Anschluss in the League of Nations.

Rafael Trujillo of the Dominican Republic famously if not quite altruistically offered his nation as a refuge to Jews. Guatemala’s Jorge Ubico is presented as both a fascist and a lifesaver to Jews in the book; former MIT professor Hans Guggenheim is quoted praising Ubico for helping members of his family escape Europe, although he turned down Guggenheim’s grandmother, who died at Auschwitz.

German Jews in Latin America also had to fear kidnapping by the US. Through a secret program, ethnic Germans and Japanese in the region — even if they were not pro-Axis — were brought to internment camps in the US, where they might be exchanged for Americans in Axis captivity. German Jews feared pro-Nazi inmates with influence in these camps — and the possibility of being “repatriated” to the Reich and a likely death.

“When you have a secret project outside the law, based on ‘race’ or ethnicity, you’re going to have these absurdities,” McConahay said.

Eighty to 90 German Jewish prisoners were relocated to a camp in Algiers, Louisiana, far from the pro-Nazi element.

“As far as I know, no one was ever traded [back to Germany],” she said.

After the war, there was a massive outflow of escaped Nazis from Germany to Latin America.

“What democratic countries were afraid of after the war was the strength of the Soviet Union and the spread of Communism,” McConahay said. “It’s not so surprising that bishops in the Catholic Church facilitated the passage of men with blood on their hands to free lives in Latin America.

“The attitude and beliefs of these churchmen were that these Fascists would be, as one called it, a ‘moral reserve’ for the future. They had experience fighting Communism. They were the last people to let themselves be conquered by Communism. Their lives had to be saved.”

The infamous cases included Adolf Eichmann, subject of the recent film “Operation Finale,” and Dr. Josef Mengele. Perhaps the strangest example is ex-Nazi Walter Rauff, identified in the book as a postwar intelligence operative for the US, Israel and Syria.

“US allies and the US wanted the kind of expertise these men had developed,” McConahay said, noting that some of them worked in American and Argentine industries and served as advisors to Latin American dictators.

And, she said, “Thousands and thousands and thousands more than these few experts went to Latin America — Argentina, particularly, and Chile, which had pro-Fascist governments.”

Rauff “died a natural death in Chile,” McConahay said. “There were lots of people who mourned at his funeral, who raised the Nazi salute as he was put into the ground.”

The controversial map shown to Roosevelt on the eve of Pearl Harbor was never realized. McConahay wonders how much it would have differed from what transpired.

“When I look at the Cold War history of Latin America, Fascist-type dictators fought reformers and democrats and Communists, all as if they were a single enemy,” McConahay said.

“Four hundred-thousand in various countries were killed in this period, the late ‘60s, ‘70s, ‘80s, mostly by authoritarian military governments supported by the US,” she said. “I wonder, for ordinary people — of course this is speculation — in what way would it have been so different if avowedly Fascist regimes had taken over the whole Southern Hemisphere?”

Artículos Relacionados: