A los 14 años le dijo a su hermana: Todos los días tienes que leer un libro, no importa si es Nietzsche, Heidegger, Freud no importa, lo importante es leer, sabes, pensar….

De entre todas las mujeres en las oficinas de Hebdo ella fue la única asesinada porque era la única judía.

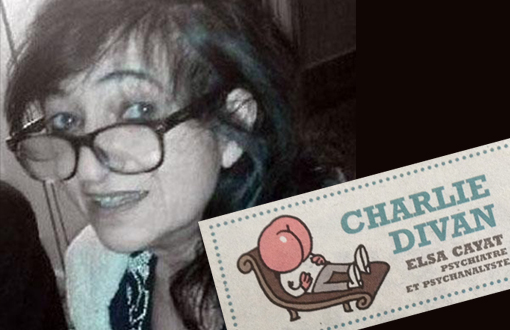

Obras:

Elsa Cayat, Un homme + une femme = quoi ?, Payot, Jacques Grancher, Paris, 1998, ISBN 2733906054}}

Elsa Cayat, Antonio Fischetti, Le désir et la putain : les enjeux cachés de la sexualité masculine, Albin Michel, París, 2007, ISBN 2226179275.

Artículos:

Elsa Cayat, Enfance dangereuse, enfance en danger ? / « En quoi la fétichisation de la science par la technocratie aboutit-elle à la négation de l’homme et à l’éradication de la pensée ? », revue de psychosociologie ‘ERES’, enero de 2007, pp. 189-202, ISBN 9782749207612 (texto en línea).

Elsa Cayat, « L’écart entre le Droit et la loi » : La maîtrise de la vie, revue de psychosociologie ‘ERES’, marzo de 2012, pp. 235-250, ISBN 9782749215693 (texto en línea)

Eulogía

Por: Rabbi Delphine

The following eulogy was given by Rabbi Delphine Horvilleur at the funeral of Elsa Cayat, in Paris, France, on Jan. 15, 2015. It is reproduced, in a translation from the French, with consent of the family.

Elsa used to begin each of her therapy sessions by saying to her patients: “So, now, tell me!”

So, I would like for us to listen to her invitation to hear other people’s words, and for us to speak, even if this cemetery is so far removed from her disarrayed office, even if the smoke from her cigarette no longer swirls in the air. Let us tell, at this place, who Elsa Cayat was, who she was for her parents, her brothers and sisters, her family, her partner, her nephews, her patients, her colleagues, for her Charlie Hebdo family, for her daughter.

We must tell how exceptionally intelligent this woman was, how vivacious she was in her wit and humor that you all knew. We must tell of the life of a woman who was out of the ordinary, as though we were telling a story—and I think she loved stories. Just as she loved books.

As a teenager she once told her sister: “You ought to read a book a day! Nietzsche, Heidegger, Freud … It doesn’t matter!” That was her minimum diet for culture and for her love of knowledge and for words, as she conceived of them.

Elsa was passionately in love with books, especially detective stories—because she adored plots and novels that you can’t put down and where the endings, she would say, let you “always discover who the killer was, and even his motive.”

What killer, what motive bring us here today to accompany her? What would she have said about this plot? Maybe she could have laughed about it, even burst out in a contagious laugh.

I know how much so many people here miss her presence: her friends, family, patients, colleagues, neighbors. She wove a web of connections with so many people, and no one could remain indifferent to her.

She created her uniqueness, her way of being beyond the ordinary in so many ways. Including in her psychoanalytic practice about which others will speak better than I. She was neither Freudian nor Lacanian. She was “Cayatian,” a school apart, the school of someone who cherished freedom to the point of continually teaching it to others, the school of someone who can peer deeply into you and tell you exactly where it hurts, who can give you words and show you how to play with them so that language can become a healing device.

Playing with words, this passion for language and debate, is, as you know, very precious to Judaism and its sages. I tell myself she could have made a very good rabbi—I hope she won’t hold it against me that I tell her this, she who was a secular Jew, a practicing atheist.

She loved stories and plots so much that I also hope she won’t hold it against me if I recount to you, in honor of her memory, a teaching from the Talmud that seems to me to say something about her.

The Talmud tells of a famous debate between the great sages in their study hall. They were debating in the way they know so well. Voices were raised and each one was passionately and fiercely defending his point of view. Imagine the atmosphere of an editors’ meeting at Charlie Hebdo, transposed to the world of the yeshiva.

Then Rabbi Eliezer said: “I’m right, I have to be right. To prove it,” he said, “may this tree immediately be yanked out of the ground!” Within a second, the tree was uprooted and transplanted a hundred yards away. The reaction of the other rabbis: a shrug of the shoulders: “So? That doesn’t prove anything!”

Then Rabbi Eliezer pursued his demonstration: “If I am right, may the walls of the study hall fall down upon us.” Immediately, the walls of the yeshiva began to crumble. The other sages turned toward the walls and said: “Why are you getting involved? This is a debate among sages; stop moving and stay where you are!” The walls stop moving. Running out of arguments, Rabbi Eliezer calls upon God himself and says: “If I am right may a celestial voice confirm it.” Immediately a celestial voice announces: “Rabbi Eliezer is right.” Silence in the study hall. Then a man, Rabbi Yehoshua, gets up and says to God: “This discussion does not concern You! You entrusted us with a law, a responsibility, now it is in our hands. Stay out of our discussions.”

That is how the rabbis of the Talmud spoke to God, with a certain lack of respect, telling him: “Don’t intervene in the debates of men, because the responsibility you entrusted to us is in our hands.”

This episode ends even more strangely, with the reaction of God. Hearing these words, states the Talmud, God began to laugh gently: “My children have beaten me!”

Why do I tell you this story? What does it have to do with Elsa? Learning how to discover her universe these last few days, it suddenly seemed to me that this story is very “Cayatian.”

It is the story of a Divine who can laugh and rejoice in an impudent humanity, a humanity that tells God humorously: “Please do not disturb—we’re in charge.”

It is the story of a God who can laugh and keep his distance, a God who rejoices when he is told: the world is “atheistic,” in the literal sense of the term, meaning that God has withdrawn so that men can act as responsible beings. This God is not the God of the Jews but the God of all those who, whether they believe in him or not, consider that responsibility is in the hands of mankind, and most particularly of those who interpret his texts. In short, a God of freedom.

In her very last article, published posthumously yesterday morning in Charlie Hebdo, Elsa wrote: “Human suffering derives from abuse. This abuse derives from belief—that is, from everything we have had to swallow, everything we have had to believe.”

Such is her final and powerful message: Be free enough to get beyond everything that has abused you—that is, everything that people have made you “drink” from their baby bottle, everything that people have made you swallow whole, without your having thought about it, re-thought about it and, above all, interpreted it. Such is the heritage of psychoanalysis, of critical thought, and (to my mind) of mature and live religious thinking.

A heritage, belief systems and texts—especially texts—are there to be interpreted, to be digested, sometimes far afield from their literal sense. Without that, they can alienate us, lock us in suffering, soak us in their abuse. They sentence us.

This very last article, this last message with its profound intelligence, is like her last therapy session, to try to help us get a little better, in the heart of tragedy.

Right now, God is perhaps already on Elsa’s couch. And she says to him: “So, now, tell me!” while the spiraling rings of smoke rising from her cigarette form clouds over our heads.

May you envelop us with your affection—friends, parents, family, and above all her daughter. May she continue to sing in the street, as she used to do with her mother. May she be nourished by the precious memory of a mother who was out of the ordinary, who loved life, and whose memory can never be killed by anyone.

According to the words of our tradition, may her memory be woven into the fabric of the living. May her story be sewn into your lives—for after all, her family name “Cayat” means “tailor,” both in Hebrew and in Arabic—and may we all together treasure the memory of a free woman.

***

Translation from the French by Ralph Tarica.

Artículos Relacionados: