03Canciones clásicas en Ladino, Yiddish y Hebreo y canciones de libertad y hermandad de compositores judíos contemporaneos:

Nuestras favoritas:

- En ladino:

http://archives.savethemusic.com/bin/archives.cgi?q=songs&search=collection&coll=7&Rank=31 - En Yiddish

http://archives.savethemusic.com/bin/archives.cgi?q=songs&search=collection&coll=7&Rank=16 - En Hebreo:

http://archives.savethemusic.com/bin/archives.cgi?q=songs&search=performer&id=Cindy+Paley

The Four Questions – די פֿיר קשיות

One Only Kid

Two of our most beloved folksongs feature a kid – a young goat: “Chad Gadya” [One only kid], the last song of the Passover seder [ritual feast], and “Rozhinkes mit mandlen” [Raisins and almonds], a Yiddish lullaby written at the end of the nineteenth century by Avraham Goldfaden (listen here).1 Is there any connection between the kid in the two songs? Is there a reason why the kid has become a part of our culture, or is this accidental? Why do we love these songs so much, and what roles have they played in the development of our folklore?

“Chad Gadya” [One only kid]

“Chad Gadya” is a cumulative song which is sung at the end of the Passover seder. It tells a story in each stanza of which another detail is added to what has come before: the kid is eaten by a cat which is bitten by a dog which is beaten by a stick which is burned by a fire which is put out by water which is drunk by an ox which is slaughtered by a ritual slaughterer who is killed by the Angel of Death who is killed by God.

Ashkenazi and Sephardic versions of “Chad Gadya“

The song “Chad Gadya” was first incorporated into the Prague Haggadah [the text for the seder ritual] in 1590, together with the second last song “Echad mi yodea?“[Who knows one?], although both songs existed centuries before they were first connected to the seder, and the Jewish origins of “Chad Gadya” may even be pushed back as far as the thirteenth century. (Rayner, p.114). It was never part of the Yemenite ritual, and a Ladino version of the song – “Un cavretico” – was only added to Sephardic haggadot from the beginning of the twentieth century. “Chad Gadya” is sung in many different languages by Jews around the world: here are Bukharan,Libyan, Tunisian and Polishversions.

Musicologist Abraham Schwadron spent ten years collecting hundreds of versions of “Chad Gadya” from Jewish communities around the world. The collection is housed in the American Folklife Center of the Library of Congress, and a disk of 25 of these recordings is available from Folkways. Voice of the Turtle, a group which specializes in Ladino music, also produced a disk – “A Different Night” – of their own interpretations of “Chad Gadya” as well as other seder songs, based upon the Schwadron collection and other sources. Performances of “Chad Gadya” by Jewish communities around the world may be heard on the “Invitation to Piyut” website.

According to Ruth Rubin: “Chad Gadya” is mentioned in Cervantes’ Don Quixote, Arnim and Brentano included it in their collection Des Knaben Wunderhorn, Heinrich Heine makes Jakel the Fool chant it in “The Rabbi of Bacharach”, and Israel Zangwill uses it effectively in “Dreamers of the Ghetto”.

Related folksongs

There are several European folksongs which incorporate the sequence of the cat/dog – stick – fire – water – ox– butcher, and parallels may be found in Persian and Indian sources, as well (Jewish Encyclopedia). Most scholars agree that the song was borrowed from a German folksong, which in turn was based upon an old French nursery song. The most immediate source may be the German folksong “Der Herr der Schickt den Jokel aus” [The master who sent the peasant out], a variant of which was recorded by the Grimm Brothers: the farmer (peasant, Jack, Yekele, yokel) refuses to harvest apples (or pears) until he is finally persuaded to do so following a series of events leading up to a higher force such as the Devil. (Watch a video of 95-year-old Lou Zeiden singing a Yiddish version of this song).

Where does the “kid” come in? Here it is, in a French folksong, “Ah! Tu sortiras, Biquette“, about a very stubborn little goat who refuses to get out of the cabbage patch. Watch the following really cute video. Another French/Catalan folk story featuring the same sequence is “La Petite Fourmi qui Allait à Jérusalem” [The little ant that went to Jerusalem]. One of the readers of this webpage, Michal Mynar, has also sent in this humorous Czech song: Jora de na pivo.

Jewish sources

The basic imagery of all these variant folksongs is that of ever-increasing strength, while the moral varies from culture to culture. The Jewish message underlying “Chad Gadya” is that there is a chain of cause and effect – those who destroy will themselves be destroyed – and that in the end justice will prevail and God will triumph. This message has, in fact, been expressed in midrashim [homiletic teachings] relating to our very earliest Biblical stories, such as the one concerning the struggle between the patriarch Abraham and King Nimrod in Bereshit Rabba 38: “Nimrod suggested to Abraham that since he had refused to worship his father’s idols because of their want of power, he should worship fire, which is very powerful. Abraham pointed out that water has power over fire. ‘Well,’ said Nimrod, ‘let us declare water god.’ ‘But,’ replied Abraham,’ the clouds absorb the water and even they are dispersed by the wind.’ ‘Then let us declare the wind our god.’ ‘Bear in mind,’ continued Abraham, ‘that man is stronger than wind, and can resist it and stand against it.’ Nimrod, becoming weary of arguing with Abraham, decided to cast him before his god – fire – and challenged Abraham’s deliverance by the God of Abraham, but God saved him out of the fiery furnace.” (To learn more about the struggle between Abraham and Nimrod, see the lecture on “Kings and Queens”: “Cuando el rey Nimrod“).

El Lissitzky – “And then came the fire …”

Another source dealing with the concept of strength relates to the giving of charity, which Jewish tradition views as the strongest force in the universe, even greater than death itself: “Rabbi Judah used to say: Ten strong things have been created in the world. The rock of the mountain is hard, but iron cleaves it. Iron is hard, but fire softens it. Fire is powerful, but water quenches it. Water is heavy, but clouds bear it. Clouds are thick, but wind scatters them. Wind is strong, but a body resists it. A body is strong, but fear crushes it. Fear is powerful but wine banishes it. Wine is strong, but sleep works it off. Death is stronger than all, yet charity delivers from death. As it is written, ‘Charity (righteousness) delivereth from Death’ (“Proverbs” 10:2).” — (Bava Batra 10a). (Diamant).

The song “Chad Gadya” has been interpreted allegorically in many ways 2, from the historical as well as religious points of view. The most common interpretation is that the “only kid that father bought for two zuzim” represents the Jewish people, acquired by God at Sinai with the two tablets of the Law (or, alternatively, through the agency of Moses and Aaron). The other characters personify nations that successively oppressed Israel, each being overthrown in its turn by a new tyranny. Assyria or Babylonia (the cat) fell to Persia (the dog), which succumbed to Greece (the stick), which was swallowed up in the Roman Empire (the fire); Rome fell to the Barbarians (the water), who were vanquished by the armies of Islam (the ox), which yielded to the Crusaders (the slaughterer). Finally, the Angel of Death represents the latest conqueror or persecutors whom God will bring to account. (Jewish Encyclopedia). There are many other interpretations: for example, the Gaon of Vilnaviewed each stage in the song as a manifestation of the battle between Yaakov and Eisav over the blessings of their father Yitzchak. R. Nasan Adler (18th century) taught that “Chad Gadya” is a warning against lashon hara [gossip] (Kaplan), and R. Yaakov Emden sees “Chad Gadya” as “a personal odyssey of self development” (Brander). (Read Kaplan and Brander for even more interpretations).

“Chad Gadya“, from the Szyk Haggadah

Songs and poetry based upon “Chad Gadya“

“Chad Gadya” has inspired the composition of many poems and songs in Yiddish and in Hebrew, especially since the 1930’s. A well-known poem by Manger, “Dos lid funem tsigele” [The song of the kid], plays upon one of the metaphoric meanings of the term “chad gadya“, signifying “prison”. Before, during and after the Holocaust, many poems, notably by H. Leyvik and Ch. Grade, utilized the image of the kid as victim. Manger’s Yesoymim [Orphans] is an elegy for both the kid, symbolizing Jewish tradition, as well as the golden peacock, symbolizing modern Yiddish literature. (For a detailed account of how the kid of both “Chad Gadya” and “Rozhinkes mit mandlen” has been treated in subsequent literature, I highly recommend this article by Menashe Geffen [in Hebrew]) It is the image of the kid as victim which was employed by Chava Alberstein in her protest song. 3 Modern Hebrew poetry includes pastoral images of the kid, in contrast to the traditional representations of the diaspora (Geffen).

“Chad Gadya” of the Haggadah has also been paraphrased as children’s songs in Hebrew and in Yiddish. We know the authors of some of these versions, but others have slipped into the realm of folklore [Songs for peysakh]. There are various “agendas” in the retelling of the “Chad Gadya” story: some are conventional paraphrases, such as the song in Yiddish by Washavsky or the Hebrew song by Uri Giv’on. Some have been secularized, ending with the shokhet[butcher] rather than with God, such as the Yiddish version by Lukovsky and Gelbart. The children’s song by Levin Kipnis is a beautiful vision of utopia rather than a chronicle of violence. (The Hebrew webpage includes links to other children’s songs).

1) Kipnis’ song, with an introduction in Hebrew by his son Shai; 2) Yiddish folk-song based on the “Chad Gadya” theme

Anomalies

One of the anomalies regarding “Chad Gadya” concerns the fact that it was translated into (faulty) Aramaic, long after this language had ceased functioning as a Jewish vernacular. (Weiss; Szmeruk). Another anomaly concerns the bottom of the ecological scale: should we be singing about a goat or a mouse? (This problem doesn’t exist in an early version of the song from Provence 4). In a well-known Italian version of the song, “Alla fiera dell’ est” [At the eastern fair] by Angelo Branduardi, the main character is, in fact, a mouse and not a goat. (Alberstein has used this melody for her song). There is a mouse in a 15th-16th century German Haggadah, but it eats the goat! (Kulp). Actually, most folksong parallels only include a cat if there is also a mouse. In Jewish tradition, it is the kid which is associated with sacrifice, and thus most appropriate to be positioned at the beginning of a chain of violent events.

Regardless of the anomalies, it is the “illogical” version featuring the cat eating the goat which most communities sing so enthusiastically every year. I personally am intrigued by what this kid means in Jewish culture and folksong and will be developing this thought in the lecture. Hope to see you there!

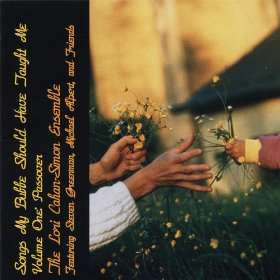

Album recomendado:

Songs My Bubbe Should Have Taught Me; Volume One: Passover

The Lori Cahan-Simon Ensemble

Comprar en línea, oprima aquí.

***

A Passover Concert: Songs of Liberation and Longing

By J.J. Goldberg

blogs.forward.com

To get us in the spirit of the Seder, here are a few songs of exodus, freedom, rebellion and an only kid. We’ve got selections by Bruce Springsteen, Chava Alberstein, Pete Seeger, Moishe Oysher, Bob Dylan, Shuli Nathan, Paul Robeson, Paul Simon, Lahakat HaNachal, the Maccabeats and many more, including two late and very much lamented friends, Debbie Friedman and Meir Ariel. Also Monty Python’s Flying Circus.

There’s a lot to tell. Tradition teaches that the Exodus was a long night, and so is the Seder. So I’m putting it up in two parts.

First up: a quick recap of the Passover story, as retold in this unusual version of the gospel classic “Oh Mary, Don’t You Weep (‘coz Pharaoh’s Army got drownded).” It’s performed by the Soul Stirrers, gospel group where Sam Cooke got his start:

Next, of course, comes “Go Down Moses.” This song has many, many unforgettable versions, but for my money there are none as powerful as this one from Preston Sturges’s 1941 film, “Sullivan’s Travels.”

It was a tough choice: I was strongly tempted to go with the unparalled classic version by Paul Robeson. I lovethis up-tempo one by the great Golden Gate Quartet. And this swinging version by Louis “Satchmo” Armstrong is a gem. All well worth a listen. But for sheer emotional power, none brings you to tears like the one below.

Background: Sullivan, a Hollywood film mogul who’s gone bumming to see the real America, gets arrested and put on a Southern chain gang. In this scene the prisoners brought to see a movie in a nearby black church. The pastor and lead singer is Jess Lee Brooks.

The Haggadah tells of four rabbis who were sitting all night in Bnei Brak recalling the events of the Passover, until their students came and said, Masters, it’s time for the morning prayers. Some commentators suggest that they were actually plotting their own liberation—the Bar Kochba rebellion against the Romans—and the students’ message was code for “make like you’re praying, the Romans are coming.” If so, here’s what that all-nighter might have looked like, from “Monty Python’s Life of Brian.”

The Magid — the portion of the Seder that retells the events of the Exodus — reaches an early emotional climax with the passage “Vehi she’amda la’avoteinu velanu” (“And that which stood firm for our ancestors and for us — for not just one enemy rose against us to destroy us, but in every generation they rise up to destroy us, and the Holy One, praised be He, saves us from their hand.”)

Here’s “Vehi She’amda” and the paragraphs that follow, sung by the great Cantor Moishe Oysher and choir. Even if it’s not your style, take a taste. There’s none better.

The exodus isn’t just an ancient story. In living memory the Jewish people were brought from a house of bondage to redemption in the land of Israel. Most didn’t make it, and those who did had to sneak across a much wider sea than Moses crossed, in an operation that would have tested Joshua. I speak of the pre-state Aliya Bet. Here’s their song (and one of my all-time favorites), “Bein Gvulot” (Between Borders) sung by Hillel Raveh. “Between borders, over impassable mountains, on dark, starless nights, we bring convoys of our brethren to the homeland. For the young and tender we will open the gates. For the old and the weak we are a protecting wall.”

And of course, the climactic moment when Moses stood on the Red Sea shore, “smotin’ that water with a two-by-four,” in the words of the old spiritual sung here by Bruce Springsteen and the Seeger Sessions Band.

After the sea closed in on Pharaoh and his army, we’re told, Miriam led the women in a song of thanksgiving (Exodus 15:20). Here’s the late and much-missed Debbie Friedman celebrating that moment in “Miriam’s Song.”

Liberation and resistance come in many forms. On the night of the first Seder in 1943, 71 years ago, the youth of the Warsaw Ghetto began their month-long uprising against the Nazis. The news of the revolt inspired a young poet in the Vilna Ghetto, Hirsh Glick, to write the Yiddish poem that became known as the Partizaner Lid or “Partisans’ Song,” also known by its opening words, Zog Nit Keynmol — “Never say you’ve gone down your final road” (lyrics in Yiddish and English here).

This is one of the greatest performances of that song. Paul Robeson gave a concert in Moscow on June 14, 1949, broadcast live throughout the Soviet Union. He had met days earlier with his friend Itzik Fefer, the great Yiddish poet who was imprisoned by the Soviets and would later be executed. Fefer told Robeson that their mutual friend the Yiddish actor-director Solomon Mikhoels had been secretly murdered the year before by Stalin’s police. Robeson decided to close the concert with Zog Nit Keynmol, which he dedicated to Fefer and “to the memory of Mikhoels,” whose death had been kept secret until that moment. Along with Golda Meir’s visit to the Moscow synagogue the previous Rosh Hashana in 1948, the Robeson concert was one of the seminal moments in the rebirth of Soviet Jewry.

This is the live recording. Listen to the emotion in his voice, and hear the audience erupt when he’s done.

The Haggadah tells us that in each generation we must see ourselves as if we had personally come out of Egypt. The fight for freedom is never over. Here are a few songs of the eternal struggle.

Bob Dylan and friends at the Newport Folk Festival, 1963: “Blowin’ in the Wind.”

The Israeli labor Zionist youth movement Noar Oved ve-Lomed, Working and Learning Youth, sings the Hebrew version of the socialist anthem, “The Internationale” (English lyrics here).

Pete Seeger and the Almanac Singers, “Which Side Are You On?” Written in 1931 by Florence Reece, whose husband, United Mine Workers organizer Sam Reece, was a leader of the union struggle in the coal mines of Harlan County, Kentucky. Reece targeted by Sheriff J.H. Blair and mineowner strongmen and barely escaped.

“Standing Before Mt. Sinai,” the stirring song of the 1956 Israel-Egypt war. “It’s not a fairy-tale or passing dream, my comrades. Here before Mt. Sinai the bush still burns. And it burns in the song in the mouths of brigades of young men, before the gates of the city, in the hands of the young Samsons. Oh, the flame of God in the eyes of youth, in the roar of engines. This day will yet be retold, of how the people stood again at Sinai.”

Had enough? Here’s Dayenu (“It Would Have Been Enough”), in an excellent bluegrass rendition:

And a reimagining of Dayenu in a parody of Cee Lo Green’s “Forget You,” sung by the Fountainheads of Ein Prat yeshiva.

At last, the meal. Here’s Second City Television’s madcap version of the Passover meal, starring Eugene Levy as the father, Joe Flaherty as the reverend and, sitting next to Flaherty, the late Harold Ramis as the elder son.

Artículos Relacionados: