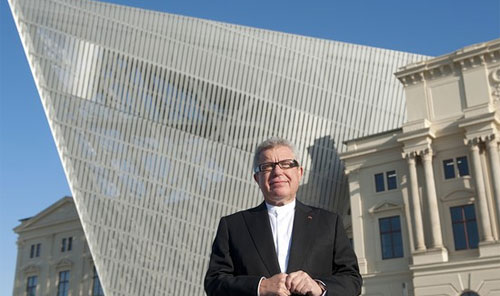

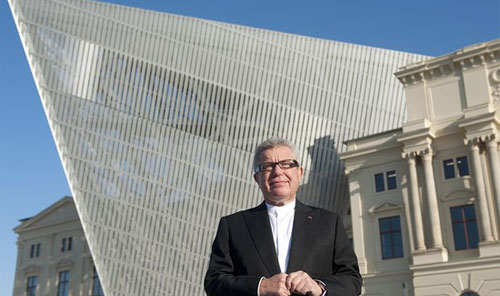

US architect Daniel Libeskind poses prior to the official re-opening ceremony in front of

the Museum of Military History in Dresden, eastern Germany, on October 14, 2011.

DRESDEN–Polish-American architect Daniel Libeskind’s newest project is an extension to the German Military History Museum (MHM) in Dresden, the official museum of the German Bundeswehr that opened last Friday. It was an interesting choice for the master planner for the World Trade Center site, who catapulted to fame in 2001 with his design of the Jewish Museum in Berlin.

Speakeasy talked to Mr. Libeskind about this seeming incongruity, and how architecture can help the world debate the role of the military in society.

Read WSJ’s profile of the museum here and our interview after the jump.

Speakeasy: 85 members of your family were murdered by the Nazis and your architectural ‘breakout hit’ was Berlin’s Jewish Museum. As a child of two Jewish Holocaust survivors, is designing a German military museum not an incongruity?

Daniel Libeskind: Precisely because I’m a child of Holocaust survivors, I had no qualms about a museum that seeks to introduce audiences to the fact that military history has changed [and] about the importance of a military for democracy. If Germany had been a democracy, those horrors never would have happened.

Your parents have both passed away, your mother in 1980 and your father in 2001. Would they have been happy you took on this project?

Yes, they were not people who only looked backwards. They had an optimism. They believed in liberty and freedom. When he passed away, my father believed Germany had a new generation of people: it was not the same Germany he knew in those horrible years.

Do you enjoy putting your “mark” on an old building, or is it more limiting than building from scratch?

I’ve been fortunate to [work on extensions] and I find it to be a dialogue with history…You get to ask new questions with a completely new space…It’s part of communicating with the past and the future together.

You built a very modern extension over what was Kaiser Wilhelm’s 19th century armory.

When I started with the building, the armory itself was really a ruin. The columns had been cut off by East Germany. The windows were walled over. My notion was how to bring back to life this important armory.

But Kaiser Wilhelm opened the armory to brag about Germany’s military might. Many people, upon hearing that a symbol of German military aggression is crumbling, would think that’s a good thing. How does your architecture help repair the building while sending a new message that the modern Bundeswehr is different?

In the competition, all the other architects built in the back of the armory. I said ‘no.’…I wanted my building to penetrate the opacity of the armory’s rigid structure…The military of today’s democratic Germany is not the military of Germany’s past. That’s exactly what the building says [now]. Looking at the building, you see this original symmetry, but then this shift in axis.

So, is your architecture therapeutic? Do you then see your part in this as helping show the world that Germany is now complete and whole?

Germany isn’t complete and whole. Nobody is complete and whole. Germany is dealing in this building with a past that is an irreversible catastrophe—a history that will never go away. But they are confronting it, and that’s different from Austria or some other places.

You’ve often said you want your architecture to serve a ‘dual purpose.’ Bringing something new architecturally while helping the original building tell its story. How does the extension’s 99-foot high viewing platform do that?

From the platform you see a Dresden that rose from the ashes of its bombing. You think of the bombings of Coventry, Rotterdam, Wielun, Poland—where I come from…Seeing this requires a connection [from] the visitor. Here, where many evils were once perpetrated, this country has the potential in the new Europe to be a force for good. This is not a museum that celebrates war—not at all—it’s a paradigm shift. It asks questions: Why is there organized violence? What happens to civilians?

What was one of your favorite museum objects?

I saw the toys [in the “Children and Toys” exhibition] and even my kids played with Transformers, Playmobil, all those things, and I saw the little melted toy tank from the bombings of Dresden. It’s still not over, the way we need to think about war and what violence means [for children].

A potpourri of intellectuals and politicians spearheaded the Jewish Museum project. You’ve said that made it difficult to reach a consensus on where your design should go. I imagine working with military leaders would be far more regimented.

I had a fantastic dialogue with the Bundeswehr and the Defense Ministry…Working with the military, you’re working with people who are brave, fly airplanes, go in submarines, once they make a decision they understand what it entails—it’s not a lot of to-and-fro and hand-holding. It’s organized like a [military] mission.

The last part of the museums chronological exhibition deals not with completed history but with history in the making—the German army’s involvement in Afghanistan. We see the voting card of Chancellor Angela Merkel who as a parliamentarian voted in 2004 to send troops there. That sits next to a German vehicle sprayed with bullets only a few weeks later.

I think it’s good to inform people that, in a democracy, the people who participate understand what’s happening. They are not just silent witnesses…There are ongoing conflicts and… it’s good that people are confronted with disturbing questions. This is not a museum that celebrates war…There will never be a time without war, we just need to steer these conflicts to a better horizon.

Artículos Relacionados: