From 1937 to 1941, approximately 1,200 European Jews escaped to the Philippines to escape the Nazis, only to find themselves facing another bloody war under Japanese occupation.

Many of these Jews came from Austria and Germany, since the anti-Semitic laws, such as the Nuremberg race laws, escalated. Since many Jews were unable to move to countries like the United Kingdom and the United States, thousands of Jews instead went to places like Shanghai in China, Sousa in the Dominican Republic, and Manila.

Those who came to Manila had no idea at the time that they escaped the Holocaust only to be caught in the midst of the war on the Eastern Front, where the Philippines came under attack.

“We were going from the frying pan to the fire,” Lottie Hershfield, a Holocaust survivor who left Germany at age 7 with her family to go to the Philippines to escape the war, said to CNN. “We went from Nazi persecutors to the Japanese.”

Manila was saved after an exhausting, month-long battle in the Battle in Manila, which is now known as one of the deadliest battles of World War II and just celebrated its 70th anniversary.

This relatively unknown period of history about Jewish refugees in the Philippines has influenced two documentaries and discussion of a possible movie.

“We know about stories like Anne Frank, ‘Schindler’s List’ — the things that grab popular imagination,” said Michelle Ephraim, whose father, Frank Ephraim escaped to the Philippines after Kristallnacht in 1938, to CNN. “Once you bring an Asia element, it becomes so complicated, interesting and surprising.”

According to documentary filmmakers, approximately 40 of the Philippines refugees are still living. These refugees were children when they came to the Philippines over 70 years ago.

“That was like a rebirth,” said Noel Izon, the filmmaker of the documentary, “An Open Door: Jewish Rescue in the Philippines,” in which he interviewed several Jewish refugees, to CNN “They went from certain death to this life.”

Among those interviewed was Frank Ephraim, a refugee who came to Manila at eight years old. Ephraim told of his experience in his biography, “Escape to Manila: From Nazi Tyranny to Japanese Terror.”

“My father got a lot of positive attention, coming from a place where Jews were exiled and treated so poorly,” said his daughter, of his escape from Europe, to CNN. Frank Ephraim died in 2006.

“The Filipinos were incredibly kind and treated him extremely well. There was an element of something so redemptive.”

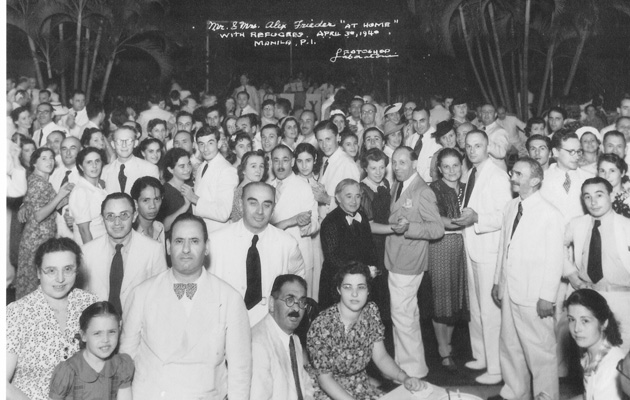

The first president of the Philippine Commonwealth, Manuel Quezon, and a group of Americans that included future U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower and the Freiders, the Jewish-American brothers, became increasingly worried about how Jews were being treated in Europe during the 1930s.

“They had a shared view of the world, they were men who understood what was happening in Europe,” said Russ Hodge, co-producer of the documentary “Rescue in the Philippines,” to CNN. That documentary was shown in the Philippines with the country’s president, Benigno Aquino in attendance last year.

Over a game of poker, the men came up with a plan to bring Jewish refugees to the Philippines.

The Philippine Commonwealth was still under U.S. supervision so it could not accept people in need of public assistance. The refugee committee decided to look for highly skilled professionals like doctors, mechanics, and accountants.

By 1938, a succession of refugees arrived in the Philippines, including a rabbi, doctors, chemists, and even a conductor, Herbert Zipper, who had survived the Dachau concentration camp and would later go on to found the Manila Symphony.

Quezon’s goal to bring 10,000 Jews to the southern island of Mindanao was ruined when World War II came to the shores of the Philippines.

For the European Jews who came to the Philippines, “it was a cultural shock,” said Hershfield. “We didn’t know the language. We had never seen any other than white people before.”

This land had thick humidity, overpowering heat, and gigantic mosquitos.

However, the young Jewish refugees soon began to view the Philippines as a new adventure. Children would scale mango trees, swim in the bay, and learn Filipino songs.

Herschfield befriended the local neighbors, played sipa, which was a local kicking game, and adored tropical fruits like papaya and guava. For Herschfield, life in Manila was being able to go around in summer clothes and sandals, but her parents had a very different experience.

“It was very difficult for my parents,” she said. “They never really learned Tagalog. They had been westernized and they stayed mostly within their circle of other immigrants.”

Many of these Jewish refugees lived in crowded community housing where fights constantly broke out. These immigrants had gone from being wealthy in Germany to having nothing in a very foreign land.

“It wasn’t what they’d known before in Germany,” Izon said. “At the same time, they were able to practice their religion, able to intermingle and have businesses.”

Herschfield’s fun-filled days of playing under the Manila sun came to a sudden end as World War II came to the Philippines.

The Japanese first began to occupy the Philippines in 1941. In some ways, the Jewish refugees were given much better treatment than the Filipinos. The thing that ironically kept the Jews safe was their German passports with the swastika, which made the Japanese view the Jews as allies.

“It occurred to me later, that’s what kept us from being interned,” said Ursula Miodowski, who was 7 years old at the time, to CNN.

The Japanese interred British and American residents in camps and Filipino and American soldiers were coerced into marching 65 miles in the infamous Bataan Death March, in which approximately 10,000 prisoners died.

Japanese officers seized residents’ homes and also stockpiled crops for its military. The local economy fell apart and food was hard to be found.

Surviving refugees said that life under the Japanese was tough and brutal.

When Allied forces began reclaiming the Philippines, bombs began to fall on a daily basis. Families were forced to hide in bomb shelters and had no idea when the next bomb would fall. Frank Ephraim spent days hiding in a ditch, where he was shaking with only a mattress covering his head for shelter. One of Herschfield’s friends was killed after stepping on a mine.

“Fires were going on all the time,” said Hershfield. “You could see the black clouds, smell of bodies, lying there and decaying.”

As the Japanese began to lose Manila, the imperial troops began a vicious urban campaign. Rapes, torture, beheadings, and bayonetting of civilians were widely reported, to the point where a Japanese general Tomoyuki Yamashita was later killed for being unable to control his troops.

“The Japanese decided to destroy Manila. They were going to give them a dead city, they set about doing that,” said Miodowski. “They burned, they killed.”

However, war time in the Philippines was “preferable to being in a concentration camp,” she said.

The month-long urban street fighting for Manila left the city ruined, as it destroyed its economy and infrastructure. The Philippines had almost a million civilian deaths during World War II.

Despite the fact that she had to suffer through the trauma of seeing the war on both fronts, Herschfield is grateful.

“We would not be alive today if not for the Philippines. We would’ve been destroyed in the crematorium,” she said.

Israel constructed a monument honoring the Philippines at the Holocaust National Park in the city of Rishon Lezion in 2009. The monument, which is shaped like three open doors, is there to thank the Filipino people and its president for harboring the Jewish refugees during the Holocaust.

Many of the descendants of the Jewish Holocaust refugees who escaped to the Philippines have not failed to remember their family’s place of shelter.

Back in November 2013, when Typhoon Haiyan hit the Philippines, workers from the American Jewish Distribution Committee came to help.

Danny Pins, who is related to Herschfield and is the son of a Jewish refugee to the Philippines, was at the head of its assessment team.

“For me it was like coming full circle and I couldn’t help but think of what it must have been like when my grandparents and mother arrived 76 years ago,” he said to CNN. “My going to the Philippines after Typhoon Haiyan was very special. I was repaying a debt to the country that saved my family.”

Artículos Relacionados: