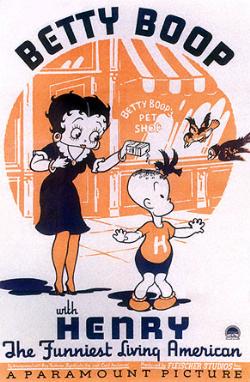

The American dream might read something like this: two brothers from a family of five, one an immigrant, one born soon after his mother sailed to New York and came through Ellis Island, rebel against their Old World parents, refuse to finish school, and instead enter the less-than-respectable world of movie-making in a less-than-respectable field: animation. Against all odds and expectations and due to an ingenious invention they do more than make good. They become Hollywood movie moguls with a studio which produces films starring some of the most famous leading actors of the 30s, none of whom requires a salary or dressing room, and none of whom ever breaks a contract. The Fleischer brothers, Max and Dave, created and controlled one of the great 30s sex symbols, animated Betty Boop. Betty’s cartoons, remembered most vividly for their overt sexuality and often grotesque imagery, are even more provocative when viewed in relation to the lives of her working-class, Eastern European immigrant, Jewish creators.

It is Betty Boop, the Fleischers’ first sound film star, who interests us here. Encapsulated in the story of her cartoons, and in the cartoons themselves, is the reality behind the American Hollywood dream, the real relationship between Eastern European, Yiddish-speaking Jewish immigrants to America and cinema, a relationship that produced both the international success of mainstream Hollywood and also the more narrowly distributed films of Yiddish cinema. Endowed with speech, Betty Boop and her friends were able to speak to these two very different audiences: in English, the Boop cartoons were distributed all over the US. What Jewish, Yiddish-speaking audiences discovered when they attended the movies, however, was that Betty’s cartoons also spoke the language of the Yiddish cinema. That language included not only bits of actual Yiddish but also references to the themes of the Yiddish cinema and the lives of working-class Jews jammed together in tenements on the Lower East Side.

The technological development of early American cinema is often linked to the simultaneous economic development of this lower-class immigrant audience, and the Jewish audience of New York’s Lower East Side in particular, as if cinema itself embodied in its form the very rules for progress to economic and social success in America. Betty Boop’s creators, the sons of a poor inventor and his wife, are themselves seeming proof for this assertion.(4) Here, however, there is a profound disjunction between the mythical origin story of American cinema and its actual one. The narrative cinema we have come to recognize as our basic cinematic form developed almost in spite of this immigrant group, which had found its own form of entertainment in the bawdy short films of the first decade of cinema. Film historians Noel Burch and Miriam Hansen both support the characterization of the early American film audience as mainly working-class and, in its first and largest market, New York City, largely immigrant. The Fleischer brothers, growing up on the Lower East Side during the first 15 years of cinema, would have had access to the largest concentration of movie houses in the world.(5) By 1908, halfway through the reign of the nickelodeon, “nearly a fourth of Manhattan’s 123 movie theaters were located amid Lower East Side tenements, with another 13 squeezed among the Bowery’s Yiddish theaters and music halls, and 7 more clustered in the somewhat tonier entertainment zone to the north at Union Square.”(6) Jewish, primarily Yiddish-speaking, patrons, joined by the Italians, Irish, and other immigrants squeezed into housing nearby, were the single largest localized community of early moviegoers.

In contrast, the first 10 years of cinema consisted largely of vulgar exhibitionism, and film gained a reputation as the type of entertainment uptown vaudeville audiences could not attend. Once the first producers began to see large returns on their investments in film, however, they hoped to break into the mass audience which supported vaudeville.(9) In order to share in the revenue and social status enjoyed by vaudeville theater owners, cinema purveyors had to eliminate strip teases, violent slapstick, peephole scenes, cross-dressers, and prize fights–all the most popular attractions on their bills. Trying to find new material, cinema moved away from the “cinema of attractions,” characterized by a number of short, spectacular films, and towards narrative.(10)

The movie theater owners soon discovered it was not enough to change the subject matter of their films from peep shows to uplifting narratives. Although they began to attract some middle-class patrons, particularly women, few attended openly.(11) The real problem was the nickelodeon theater itself, another result of cinema’s birth in the slums of big cities. An affluent, respectable mass audience would not patronize the early cinema less because the films were unappealing than because of the theaters themselves:

Within two or three years nickelodeons were perceived by middle-class reformers as `the core of the cheap amusement problem,’ not only because they drew by far the largest crowds, but also for the unprecedented hazards that lurked between the flickering screen and the darkness of the theater space.(12) The reformers likened the nickelodeon theaters to “prostitution and working-class drinking,” other sins that needed to be eliminated from the cities.(13)

Still, during the years of the, cleaning up process, the original cinema audience, the immigrants and working-classes, didn’t abandon cinema. The more genteel audiences the theater owners hoped would appear also did not materialize until the early teens. Thus, for a number of years the cinema played primarily to audiences its films did not address. The vulgar displays which were purged first from vaudeville and then from cinema reflected the amusements of people with little money who lived on top of one another. Sex and violence, while relatively easy to keep undercover and behind doors in a middle-class neighborhood, were unavoidable in neighborhoods where thousands of people lived in a tiny area.(16) Betty Boop herself, frequently the object of both sex and violence, was an inhabitant of this world. In one of the first Betty Boop cartoons, “Any Rags” (1931), Betty hangs out of her tenement window to flirt with the ragman. This cartoon is only one of a number of films in which Betty contends with the hazards of life as a single girl in the big city.(17)

What would be funny or familiar to this audience would be the sorts of jokes or scenarios which resulted from opening doors at the wrong time, drunkenness, practical jokes, amusements which required little money, no travel, and no extra implements besides the brain and the body, the attractions the Fleischer,; would bring back to film with Betty Boop: her dress slipping down to reveal her bra, for example.(18) The stories of travel or middle-class love affairs which came to dominate the nickelodeon playbills certainly would have been comprehensible to the tenement audience, but the films no longer reflected their reality.

Burch claims that cinema’s new reliance on vaudeville precipitated this disjointed address because of language and cultural difficulties, problems more of national origin than of class:

Let alone its specifically xenophobic content, a form such as the minstrel show, for example, born three decades before the first great wave of immigrants, quickly became a highly coded spectacle, shot through with cultural allusions only meaningful to native Americans and depending to an important extent on wordplay.(19)

If the vaudeville-based subject matter was truly incomprehensible to immigrants steeped in the culture of the Eastern European shtetl, it seems likely that the theaters would have closed and the audience, lacking entertainment, would have disappeared altogether. In addition, in the presound era, exhibitors could replace English title cards with title cards in Yiddish, or an enterprising bilingual audience member could translate them out loud, thus negating the language difficulties of films based on wordplay, though, of course, double entendres and slang would likely be lost.

Miriam Hansen tries to explain this audience’s loyalty to cinema by suggesting that the poor, overworked, crowded residents of the Lower East Side would have attended the cinema regardless of the product being shown:

The nickelodeons filled this market gap with their low admission fee (a vaudeville ticket cost twenty-five cents) and flexible time schedule… The nickelodeons offered easy access and a space apart, an escape from overcrowded tenements and sweatshop labor, a reprieve from the time discipline of urban industrial life.(20)

So why did the immigrant audiences remain so loyal to the cinema? The reality of the nickelodeon more likely offered to the immigrant something different than either Burch’s incomprehensible storylines or Hansen’s idyllic theaters. The nickelodeons offered a low-priced, convenient, enjoyable enough form of entertainment that immigrant audiences would attend even if the shows were not entirely comprehensible. These shows were not, however, completely incomprehensible either; the Yiddish-speaking immigrants were learning American customs and cultural codes on a daily basis (as well as influencing them), and the narratives relied for the most part on stories that were very similar to the same sorts of stories these immigrants might read in their native languages–love stories, for example, or slapstick comedies for which the humor was mostly visual anyway.

The lack of direct address did have an impact on these audiences, though the extent to which the new content propelled them into middle-class respectability is perhaps overstated.(21) Probably the most lasting effect of these narratives was encouraging assimilation and the loss of ethnic markers in its audiences. The tamer humor from the vaudeville stage reproduced the latest craze–the shtick of comedians making fun of newly arrived ethnics, a much easier translation to the silent screen than the more traditional vaudeville act, the musical blackface minstrel show.(22) Very quickly the avaricious Jew, the drunken Irishman, and the dull-witted Swede began to populate the cinema, replacing African-Americans as the new American Other. Eventually the minstrel show was replaced with silent set pieces featuring the lazy, criminal-minded Negro alongside the immigrants; James Stuart Blackton’s “Lightening Sketches” (1907), which turns the words “coon” and “Cohen” into caricatures of their namesakes, is the paradigmatic example of this combination.

Early narrative film depicted the immigrant as Other even as it played to an immigrant crowd. For example, in Skyscrapers “it is unmistakably the immigrant who is the Other, and his extreme perversity–he is quarrelsome and treacherous… propels the action.”(23) The Yiddish community was no exception: The anti-Semitic “cliches, which had easily found their way into early films (such as Cohen’s Advertising Scheme [Edison, 1904], Cohen’s Fire Sale [Edison, 1907], and Lightning Sketches [Vitagraph, 1907]), had survived most vigorously in slapstick comedy, a genre defined by caricature and exaggeration.”(24) It is not difficult to imagine that audiences who identified with the caricature on screen would try to distance themselves from it. The most longed for resolution was to transcend the working-class altogether, but often animosity was displaced to another ethnic group. Burch even proposes that it was this portrayal of the immigrant Other in early film which solidified the American history of interethnic hatred.(25) The Betty Boop cartoons provide evidence for the impact of these cinematic stereotypes into the cinema of the 30s. Clear references to Yiddishkeit found in the cartoons reveal a degree of comfort with their cinematic image enjoyed by those Jews whose success provided some distance from the typical anti-Semitic stereotypes. The cartoons are not as kind to other ethnic groups, however, and the stereotypically racist depictions found in cartoons like “Mask-A-Raid” (1931), which spoofs Italian and Chinese immigrants, emphasizes the long-lasting effects of these widely distributed and frequently repeated caricatures.

Betty Boop is a result of the sound era and the ability to bring popular music and dance to the cinema screen. Before sound brought the possibility of reinstating the minstrel show, however, the immigrants on the Lower East Side responded to the popular “soft racism”(27) of the film comedy sketches with local theatrical entertainments, novels and newspapers aimed at and created by the immigrants themselves. Soon an alternative cinema had also developed in response to the demands of the community. During the teens and early 20s, immigrants to the Jewish, Yiddish-speaking community centered on the Lower East Side, which already had a popular and economically viable Yiddish theater, brought with them an understanding of film and a desire for self-representation, the prerequisites for a Yiddish cinema.

In Europe, most notably in Russia’s Pale of Settlement, home to more than half the world’s Jews when cinema was invented, film distributors and projectionists soon recognized a specifically Jewish audience for film. J. Hoberman tells a story which bears repeating here:

[Francois] Doublier, [a teenaged employee of the Lumieres] arrived [in the Pale] at the height of the Dreyfus affair, shortly after Emile Zola’s second conviction and the sensational suicide of confessed forger Major Hubert-Joseph Henry had further stimulated an already intense interest among Russian Jews. Not surprisingly, the Jews of Kishinev wondered about the absence of Dreyfus material in Doublier’s presentation. The young showman didn’t have to be asked twice. By the time he reached Zhitomir, his program included an extra attraction. Anticipating the montage experiments of Lev Kuleshov, Doublier assembled a new movie, splicing together four shots–a French military parade, a Paris street scene with an imposing building, a Finnish tugboat meeting a barge, and a panorama of the Nile delta. These, he informed spectators, presented Dreyfus before his arrest, the Palais de Justice where Dreyfus was court-martialed, the boat that took him to Devil’s Island, and finally Devil’s Island itself.(28)

It was an immediate hit. Doublier had responded to the desires of his market by producing a film specifically for it, even though that film claimed to show the events in the Dreyfus case of 1894, more than a year before the cinematographe was even invented.(29) Hoberman sees this willingness to believe in the veracity of the film as an indication of the power of the film medium, but this incident also points out that this particular early film audience was not so amazed and stupefied by its first glimpse of cinema that it could not place demands on it.(30) The Yiddish-speaking audience of the Pale recognized cinema as a medium which could carry messages as well as entertain and one which could be controlled by the consumers as well as the producers.

As early as 1911, Yiddish films were being produced for this population. Fifteen years after the invention of cinema, Jewish entrepreneurs were beginning to become a greater part of what had been, contrary to the prevailing myth, the almost entirely non-Jewish world of filmmaking.(31) The Hollywood of American cinematic: myth populated heavily by Jews was born in the late teens. During the earliest days of Yiddish cinema Hollywood was only a shooting location for Westerns. As the large number of theaters in New York’s Jewish neighborhoods attests, instead of producing and directing, the earliest Jewish film pioneers did in America what other Jews in the film industry were doing in Europe: parleying the experience of being itinerant merchants into the distribution and exhibition of films.

By 1924, fleeing pogroms and persecution, nearly half the Jews in Yiddish-speaking communities in Eastern Europe had emigrated to America, bringing their cinematic: literacy and tastes with them.(32) The massive immigration of these Jews to America demanded the transplanting of Yiddish cinema as well. The Yiddish-speaking audiences of the Pale not only provided a ready-made audience for the nickelodeons when they immigrated but also provided a distribution and exhibition network among the Yiddish-speaking communities in America.

Through the 1930s American products would play side by side with Yiddish ones. The Yiddish cinema the Fleischers would have attended as young men in New York was produced primarily in the Pale and created on a low budget specifically to exploit the Yiddish-speaking inner-city population. The films also did not look always look like the multireel narrative films that were being shown throughout the country by the teens. Instead, Yiddish films were interspersed with live bits of Yiddish theater long after the “legitimate” screen had begun to show films in movie houses exclusively for cinema product, having finally attracted that wealthier mass audience.(33)

Unlike other forms of early ethnic filmmaking, “Yiddish cinema would gain much in terms of technical proficiency from the widespread influence of Jews at all levels of the film industry (both in Europe and the United States)” who, conceivably, would lend their talents to helping family and friends making Yiddish films.(34) As Jewish participation in the film industry grew in the midteens, technical proficiency was not the only gain; as Hansen suggests, “Because Jews were involved in film production early on, they had a certain input in the shaping of their public image from which other minorities, especially blacks, were barred.”(35) Despite this influence, the need for an alternative cinema remained. While Jewish members of the film industry might be able to prevent overtly negative Jewish images on the screen, they were not especially interested in catering to the relatively small Jewish market on a regular basis. Yiddish cinema filled that gap, providing (melodramatic) depictions of real life in the Yiddish communities of New York and Eastern Europe as well as adaptations of famous pieces of Yiddish literature.

In reality, mainstream producers did not entirely ignore the lucrative Yiddish-speaking audience, which prompted studios to produce a small number of films like D. W. Griffith’s Romance of a Jewess (1908), which was shot on location on the Lower East Side and capitalized on Jewish themes. Romance, and films like it, sought to appeal to both the mass audience as an “exotic” film and the particular audience of the Yiddish-speaking community, but as Hansen says of it, the narration remains quite elliptical, relying on the viewer’s familiarity with Jewish marriage customs. Even if the information was supplied by the missing intertitles, the film addresses an audience probably just as familiar with the comic routines in the opening scene, which seem to have come from the setting of the pawnshop.(36)

In other words, the story would have been noticeably Jewish only because of its title, and to any members of the audience who could identify the shadkhn or, more likely, the pawnshop routine as Jewish stereotyping. For the most part Romance like other films of its sort, was a typical melodrama about a girl who wants to marry the man she loves and not the man her family wants her to marry. It was a decidedly “mass audience” product, not really addressing the audiences of New York’s Yiddish community despite its Lower East Side location shots. The Fleischers would find another way to appeal to both these audiences, one that would capitalize on exactly what Griffith left out–the specific cultural codes of the Lower East Side.

During the 20s, an alternative cinema developed within the mass audience distribution sphere, providing an outlet for a sort of “between” work aimed exclusively at neither the mass audience nor the Yiddish audience. Neither the main draw nor the main money generator at any screening, the Fleischers were able to take greater liberties with the content of their films. In 1916 they began a process with their silent cartoon star, Koko the Clown, which culminated in the Betty Boop cartoons. Max Fleischer didn’t merely appear on screen producing Koko the Clown, Bimbo, and Betty Boop out of his inkwell but also allowed these characters to carry “more or less camouflaged” indicators of their creators’ Yiddish-American background.(37) Their animated films, along with short subjects and comedies playing second on a double bill, could also address the urban audience ignored by feature films, incorporating the “cinema of attractions” style of early cinema to draw shocks and laughs from precisely the material the nickelodeons had sought to exclude from the screen 15 years earlier. The Fleischer cartoons are a prime example of a unique moment in American cinema in which a product aimed at a mass audience also reflected the concerns and culture of another cinema audience altogether–the audience, for the alternative Yiddish cinema.

Animation attracted the scientists and mechanics of the commercial art world; animators were as interested in the technical processes which made films possible as they were in actually making films. Dave and Max achieved their first real success as animators with the rotoscope, an invention developed with the help of their three brothers in 1916 between Dave’s shifts as a cutter for Pathe Freres and Max’s work as art director for Popular Science Monthly. With this invention they perfected a process for capturing lifelike movement in animated characters.(38) To create a rotoscoped cartoon character the Fleischers first shot a normal film strip of a body in motion. Dave, dressed in a clown suit, provided the initial subject matter. Next, Max and Dave used the rotoscope to magnify individual frames of the filmstrip onto a piece of glass. Then they traced Dave’s changing positions onto celluloid frame by frame, modifying his features into those of their new star.(39) Finally, they photographed each piece of celluloid onto a single frame of motion picture film. The result was the first Koko the Clown filmstrip, in which Koko’s body reflected all of the subtle changes made by a human body in motion. When their invention was brought to the attention of an old acquaintance, John Bray of Paramount, the now famous Fleischer cartoons were born, and Bray moved the brothers into Paramount’s New York studios.

Before rotoscoping, animation was alternately choppy or surreal in quality, making cartoons ill-suited to character-driven narratives. The rotoscope, and what it revealed about lifelike motion, created the possibility for the cartoons we know today; by the mid-20s, Warners, Paramount, Hearst and Columbia all had animation departments, and animation-only studios like Bray, Lantz, and Disney were in heavy production. The Fleischers were the only ones to explicitly address a Yiddish audience (though the Warner Bros. cartoons reveal a similar urban, ethnically Jewish aesthetic), and Fleischer innovations, including experiments with 3-D sets, color, and sound would keep Koko and his friends (eventually to include Popeye the Sailorman and Superman) among the most technologically advanced films of the 20s and 30s.(40)

The Fleischers themselves starred in their innovative cartoons alongside Koko. Animation had long featured the animator himself as subject of the films; in the earliest animations, the animator and his magical ability to bring drawings to life were the focus of attention, like a magician whose tricks serve to focus on his abilities. The tradition of “From the Hand of the Artist” films beginning with Blackton’s portrait of Edison (1896), gave the animator a personal relationship with both his animated characters and the audience that live-action film directors, usually invisible, did not have.(41) Donald Crafton explains that the early animated film was the location of a process found elsewhere in cinema but nowhere else in such intense concentration: self-figuration, the tendency of the filmmaker to interject himself into his film. This can take several forms; it can be direct or indirect, and more or less camouflaged… But this tendency, which persisted throughout [the years 1898-1928], seems on the evidence of the films’ contents and the memories of veteran animators to be real and conscious. At first it was obvious and literal; at the end it was subtle and cloaked in metaphors and symbolic imagery(42)

This tradition of the animator on screen remained even after stop-action photography made animation as we know it possible, and in 1909 Emile Cohl expanded the ability of the artist to interact with animated characters when he introduced matting as a technique for combining the live-action animator and his creation as separate entities within the frame.

Through matting Koko, not the Fleischers, became the seemingly autonomous star of their cartoons as he moved back and forth between the live-action world and an animated one. But even though the artists were no longer necessary in every shot, the Koko cartoons still emphasized the character’s creators. They titled Koko’s 1916-1929 series Out of the Inkwell, and each cartoon began with Max bringing Koko to life at his drawing board. Koko doubly inscribed the Fleischers in their films as both their creation and as Dave’s animated alter ego. He was a personal character and as such his; cartoons often contained references to Max’s and Dave’s own personal background in the Yiddish culture of New York’s Lower East Side, a self-reflexivity less possible in feature filmmaking. By the time Betty Boop appeared in 1930 the transition Crafton cites from literal to cloaked self-figuration had been made. In over 100 Betty Boop films from 1930-1939 Max only appears in one (“Betty Boop’s Rise to Fame” [1934]), and Dave in none. The transfer of animator to character, literalized in the Out of the Inkwell series, is more subtle in Betty Boop’s cartoons, integrated into the films themselves.

The Fleischers’ films, products of their Yiddish-American background, reflected the seductions and fears of assimilation for the twentieth-century Jew in a peculiarly American way. Only in America were Jews allowed to choose whether or not to assimilate completely and know that they were choosing to leave their culture behind. What J. Hoberman notes as a “bitter ambivalence” in Yiddish film is a recurring theme in the Fleischer cartoons.(43) Film after film in the Yiddish cinema depicted a difficult America which offered Eastern European Jews opportunities they had only dreamed of but which seemed to demand complete assimilation as its price. The cost of that bargain created characters who belonged fully to neither community, American or Jewish. The theme is particularly strong in one of the earliest Fleischer Talkartoons, “Bimbo’s Initiation” (1931), probably one of the most disturbing cartoons the Fleischers ever made.(44)

Bimbo, beckoned forward by an unidentified Betty (“Bimbo’s Initiation” precedes the cartoons which give Betty a marquis credit), finds himself in a secret clubhouse. He endures a series of humiliating and painful initiation rites at the hands of black-hooded figures, all the while insisting that he does not want to join their club. He is beaten, frightened, almost sliced in half, almost impaled by stakes, and then thrown down a chute. Despite his constant refusal to accept club membership, the punishing initiation continues. Finally, confronted by a weird, rubbery, undulating Betty who appears to promise herself as a prize for joining, Bimbo gives in. The walls disappear, revealing the hooded figures, who rip off their hoods and expose themselves as rows of identically dressed Bettys. A now beaming Bimbo performs a chorus-line dance with them in which he and a lead Betty spank each other in a burlesque of the initiation rites. Clearly pleased and excited, Bimbo seems to have forgotten his brutal treatment at their hands earlier.

If Bimbo represents the New York Yid and the club represents “pure Americanness” (particularly as it’s being defined at this time through a lack of ethnic markers), then this film seems to say that America offers some pretty wonderful things (rows of Bettys) if you can put up with the humiliations and confusions of initiation into the culture. “Bimbo’s Initiation” also resonates with Rogin’s argument about the function of blackface minstrelsy as a means of assimilation in the 1930s. The mark that one belongs to this society is a form of blackface–once admitted, Bimbo would presumably don his own black hood and join the chorus line of undifferentiated black America (though in this case, white America, the Bettys, is equally undifferentiated). It is significant, however, that Bimbo remains surrounded by Bettys in the end; he doesn’t become a Betty. No matter how well-initiated and happy he might be as a member of “the club,” Bimbo would still be easy to pick out from the unhooded crowd.

While the film underscores the seductive nature of white American culture, there seems to be an implicit warning here about the real possibility of shedding all your ethnic markers to the point that no one else could pick you out from your chosen crowd. Unlike Jakie Rabinowitz’s Jazz Singer, who realizes the successful transformation of Jews from immigrant group to white Americans through blackface, Bimbo, who never actually dons a black hood, is refused even a moment of total conformity in the short.(45) Throughout the Talkartoons, instead of depicting Betty and Bimbo as generic, fully assimilated American characters, the Fleischers consistently reinscribe their ethnic particularity.

“Bimbo’s Initiation,” with its unmasked appeals to sex and its depiction of graphic violence and violation, marks one of the most blatant examples of the Fleischer aesthetic, described by one critic as “broad, direct, and somewhat vulgar.”(46) This description also reflects the one Hoberman gives to the Yiddish world and Yiddish itself, the cultural source of the Fleischers material and the audience they knew best:

Yiddish is imbued with the perspective of the proster Yid (common Jew)… Earthy, expressive, marked by the experience of dispersion and marginality, and lacking the scriptural authority of Hebrew, Yiddish is neither entirely respectful or altogether respectable. For religious Jews, it is the language of the secular world; for the `enlightened,’ the signifier of Jewish insularity.(47)

“Bimbo’s Initiation,” with its strange, distorted characters and its sexual and violent content, does not directly address either assimilated Jews, who had become a part of the mass audience, or religious, purposely unassimilated Jews, for whom the content would be unconscionable. Those most directly addressed by “Bimbo’s Initiation” (and the Fleicsher cartoons in general) were the lower-class, urban, Yiddish-speaking audience of which the Fleischers had been a part and which was precisely the audience disregarded by most Hollywood films

Hoberman’s definition of the Yiddish world also suggests that the very “crudeness” of Yiddish itself was embraced quasi-politically by its speakers. For European Jews, always considered outsiders in countries where they had been settled for hundreds of years, Yiddish represented the nation which didn’t exist. Despite differences in dialect it was more than a language; it tied together Jews of different national backgrounds in a single ethnic group so that once in New York, Jews from Russia, Poland, and Austria could all converse. Drawing from this expressive language, filmmakers like the Fleischers, who had the advantage of mass distribution of a marginal genre, could include bits of Yiddishkeit in their productions as a sign of ties to the community even as the films themselves were aimed at and distributed to a more diverse, mainstream American audience.(48)

As one example of this coding, the word IvK becomes almost a leitmotif in the Fleischer cartoons. At times, as in “Betty Boop’s Big Boss” (1933), where a sign reading Iv K is seen momentarily on the top of an emergency vehicle, the kosher letters are merely an easily overlooked flash. In other instances, however, they are used to make a joke that has a secondary meaning to audiences familiar with the tradition. Betty’s screen debut, in “Dizzy Dishes” (1930), presents an enraged restaurateur being badgered by his hungry customers. Following a stream of orders, one customer, yells, “I want ham!” The restaurateur hits him with a ham that has been labeled “IvK”–a gag in and of itself, since ham could never be kosher. Another example is found in “I’ll Be Glad When You’re Dead You Rascal You” (1932): Koko the Clown is literally burning up the roads as he is chased around the world. Suddenly, the peplum of his jacket begins to bulge and a thermometer pops out of it. At first the numbers rise as expected, but then the gauge reads “?” and then “!” and finally “IvK”. The kosher sign is not only funny because the Hebrew letters are unexpected on a temperature gauge (the “?” and “!” had already provided for that joke); it is funny because the way to kasher (make kosher) a dish which is not yet usable in a kosher kitchen is to hold it over an open flame of a certain temperature. And so Koko’s IvK marks the specific temperature he has reached–he has run so fast, he is now Kosher Koko.

This joke references an entire scale of temperature and a cultural relationship to fire and food preparation which only the Yiddish audience would recognize and would appreciate as much for the insideness of the joke as for the reference to Hebrew and the laws of kashruth. While this religious reference indicated the Fleischers’ insider status to in-the-know audiences, it also marked their films as not quite ready for America’s mass audience, dangerously incomprehensible in places. This was ethnic humor which, unlike the ethnic humor of vaudeville which poked fun through broad stereotypes of Jewish immigrants, instead required fairly in-depth knowledge of Yiddish culture to get the entire joke.

In another example, “Betty Boop’s Bamboo Isle” (1932), Samoan natives greet Betty and Bimbo with a clearly enunciated “Shalom Aleichem!”, the traditional Hebrew (and Yiddish) greeting. Again, the joke is much deeper for audiences who can recognize the greeting and the incongruity of Samoan natives using it to greet other characters identified in the film as also Samoan. And perhaps it indicates a more personal incongruity for the Yiddish speaker as well, the still strange feeling of using the Yiddish language to identify other Jews in America, where there was no Pale of Settlement in which one could assume everyone would be able to make the traditional response, “Aleichem Shalom!” According to historian David Shneer there is evidence that as Jews began to leave the shtetls for Russian cities (at the same time that many were emigrating to America) “Shalom Aleichem” was used precisely as this sort of code word to identify fellow Jews from among the general Russian population.(49) Perhaps, then, “Bamboo Isle” also represents a wish that even in the most unfamiliar, uncivilized land a Jew could always find a fellow Jew.

It was exactly this inability to lose all trace of ethnicity and vulgarity which prevented the Fleischer cartoons from becoming as popular as Disney’s. By the 1930s most film had become respectable entertainment, a style embodied by Disney, whose cartoons were missing markers of any sort of ethnic identity (except, of course, white, middle-class identity). Located near the orange groves of Los Angeles, even Disney’s studio was far removed from the world the Fleischers operated in on Broadway in New York. In contrast to the starring roles of working-class characters in the Betty Boop cartoons, Nic Sammond has pointed out the decidedly villainous nature of the working-class world as portrayed in Walt Disney’s Pinocchio (1940).(50) Pleasure Island, where Pinocchio is turned into a jackass, is full of beer-swilling, pool-playing boys, who seem to have nothing better to do, have no jobs, and don’t speak Pinocchio’s accentless English (much like the crowded quarters of New York’s immigrant neighborhoods). The twenties and thirties were a period of great reform in inner-city recreation; truants were policed, city playgrounds and parks were built, and parents learned that instead of going to work, their children needed time to play, which meant toys, separate children’s spaces, and separate children’s films.(51) Sammond describes Disney’s conscious effort to be a part of this movement and to promote its cartoons as “family” entertainment which would help parents raise their children into middle-class respectability.(52) By the time Pinocchio was released, Disney had redefined animation as a children’s genre. The very adult Betty Boop, on the other hand, was a flapper, a flashy city party girl, not a respectable young lady and definitely not an appropriate character for children’s films.

The Fleischers eventually made concessions to the trend, making Betty more all-American and eliminating some of the more bizarre elements of her cartoons. In 1934, when Betty was fighting for her life as an uncensored character against the provisions of the Hays office Production Code which had drastically redefined acceptable material for American cinema (a fight she mainly lost), the Fleischers introduced Bimbo’s replacement in “Betty Boop’s Life Guard” (1934).(53) In this film Betty is paired with Fearless Freddy, who had appeared the month before as a policeman and would reappear in a series of cartoons involving Fred saving Betty from a dastardly villain. Fearless Freddy, lounging on his chair at the lifeguard station, is the epitome of American male pulchritude: dark curly hair, a slim waist, a large, well-built chest. Even in this cartoon, however, the Fleischers still made gestures toward the Yiddish community. Betty’s New York accent is particularly pronounced in this film, a decided contrast to Freddy’s characteristically melodious baritone. In addition, Betty, drowning, believes she is a mermaid and travels to the bottom of the sea, where she is met by a fish with sidecurls kvetching in Yiddish. And even Freddy, the quintessential American, is not really the hero he appears to be. Freddy the lifeguard is afraid of the cold water, and in later films, Freddy the Dashing Hero frequently fights with the villain while leaving Betty in life-threatening situations. Even his voice seems to be something of a joke. After “Betty Boop’s Life Guard” nearly all the Fearless Freddy cartoons are moved to the stage, where Betty the Virginal Homesteader, Fearless Freddy, and the Dastardly Villain all play their newest personae explicitly as fictional roles.

The original, uncensored Betty Boop was constantly negotiating her ethnic status, playing roles even as an American character. She impersonated Fanny Brice and Maurice Chevalier, danced with Cab Calloway, and was painted slightly darker to act as a Samoan in “Bamboo Isle” (1932).(54) In this latter film, Betty plays a native island girl who falls in love with shipwrecked American Bimbo. To save him from the savages (her own family) Betty helps Bimbo put on brownface, earrings, and a bone in his hair. The ruse is successful for a while, and Bimbo is treated as an honored guest. Unfortunately, a rainstorm cleans the mud off Bimbo’s face and reveals his true identity. Bimbo is run off the island, taking a smitten Samoan Betty with him. Is “Bamboo Isle” really a picture about the Samoan savage or about the ridiculousness of a good Jewish girl from the Lower East Side who wants to be a modern flapper? (Or a Samoan–is there much difference?) “Bamboo Isle” suggests that the disguise will eventually be discovered, and even Betty the Samoan is better off following Bimbo, who, having been identified as her boyfriend in cartoon after cartoon, is one of her own kind.

Are Samoans black or white? Asian or American? Unassimilable ethnic other or part of the melting pot? These themes were also concerns of the immigrant Yiddish community of the 20s and 30s, their numbers the catalyst for the worst anti-Semitism in American history.(55) Even the silent Koko cartoons reveal this anxiety, dealing with the racial traces of skin color and accent. An Out of the Inkwell film, “Chemical Koko” (1929), shows a chemist conjuring a magic potion. He summons a black janitor who drinks the potion and turns into a white man who immediately throws away his mop, smiling, enacting the transformation from unwanted Other to successful American. In a late compilation of Betty’s star-turns, “Betty Boop’s Rise to Fame” (1934), the chosen segments are the passing-drag impersonations: Fanny Brice (as an Indian maid!), Maurice Chevalier, Betty’s dance with Cab Calloway, and her Samoan dance. For this last segment Betty makes the blackface of “Bamboo Isle” explicit, returning to the ink bottle and drawing out enough ink to stain her skin slightly darker for the Samoan hula, reversing the janitor’s transformation. “Betty Boop’s Rise to Fame” was also a mid-1934 attempt to salvage some of Betty’s original pre-Code persona. Through a compilation of older, pre-Code films the Fleischers were able to present Betty at her sexiest: topless in the Samoan dance, in male drag as Maurice Chevalier, and frequently naked behind screens and an inkpot. This is also one of the last cartoons to feature her signature garter.

Betty’s body, ethnic or not, is the focus of her appeal. From her earliest films, like “Silly Scandals” (1931), “Bimbo’s Initiation,” and “Dizzy Dishes” she is all body, all titillation. In fact, as in the compilation film where she has to “change” costumes, most of her purpose seems to be in being undressed. Interestingly enough, however, the first film in which Betty appears as a distinct character with a personality, “Minnie the Moocher” (1931), marks this sexy cartoon character as Jewish and also marks her body as the source of conflict even within her Jewish home. The cartoon opens with Betty and her parents sitting around a dinner table about to eat. Her father comes complete with a Yarmulke-shaped bald spot, and both parents speak with heavy Eastern European accents. Before any image appears we hear her father beating on the table as he yells, “Vy don’t you eat? Vy don’t you eat?” while her mother exhorts her to eat her sauerbraten. This is obviously a common scene in the household; as he threatens to throw her “haus-out,” Betty’s father turns into a Victrola phonograph which keeps playing his complaints.

The parents yell, and Betty just cries–the heavy food her parents are used to, and which will produce a proper yidishe mame, would ruin the figure of a girl like Betty. Betty, certain they will never understand her, runs away and goes to hide in a cave. Cab Calloway in the form of a ghostly walrus chases her, scaring her back to her parents’ house, where she buries herself under the blankets. Focussing on Betty’s figure, “Minnie the Moocher” also repeats one of the main themes of American Yiddish cinema, the conflict between Old World and New as generational conflict, between Betty who dreams of joining the world outside her home and her parents who have already decided how her life should be led.(56)

Betty ends up back home at the end because she’s scared of an unfamiliar body–Cab Calloway, whose black body is here converted into a white spirit (as it will be when he again frightens Betty in “Snow White” [1933]), not as the jazz musician that one would expect Betty’s flapper persona to like. He is altogether different in the outside world than on a record–too frightening–and she returns to her parents, who are certainly less than sympathetic characters. The world outside Betty’s home is a world of ghosts and spirits, not of flesh-and-blood people, black or white. This is a world she has no idea how to inhabit. Her final realization that home is where she belongs seems to suggest that as much fun as life out there is, in the end the only national and personal security the Yid can count on is in his own family. And one way to remain in that family when you’ve achieved success in the wider culture, the Fleischers found, is to continue to address it more or less obviously in your films. The overt Yiddish references seem intentional, the thematic similarities to Yiddish film much less so, but the Fleischer cartoons reflect the not-quite-assimilated (or not willing to be and yet always wanting to be) status of the American Yid.

In the post-Code films Betty loses the ability to see ghosts and becomes a perfectly respectable young lady with a dog as a pet instead of as a boyfriend, impish nephews, and longer, less-revealing dresses. Soon her costars, like puppy Pudgy and crackpot inventor Grampy, take over as stars of the Fleischer cartoons, and Betty herself disappears by 1940. Mae Questel, Betty’s voice from 1931 to 1939, remarked that “Betty Boop ended when the studio moved to Florida [in 1938] and she was unable to move from New York.”(57) Questel was referring to herself, but she might as well have been talking about Betty. The Code had cut her off from her urban background five years earlier, and the move of the Fleischer studios merely confirmed that she was out of place in contemporary cinema.

Betty Boop was often compared to Mae West–another screen sexpot who lost her sting in post-Code Hollywood, but perhaps she should have been compared to the first sex-symbol of them all, Theda Bara, another good little Jewish girl who became a Hollywood star and an American fantasy.

Source: findarticles.com

(1.) Though I won’t discuss the Popeye cartoons here the early cartoons are also replete with Yiddish phrases and Jewish references.

(2.) Edison patented his peephole kinetoscope in January 1894. Film projection was invented in 1895, and by 1896 projected short films were being shown throughout the world.

(3.) Miriam Hansen, Babel & Babylon: Spectatorship in American Silent Film (Cambridge, 1991), 71.

(4.) Unless otherwise indicated, biographical information on the Fleischers is drawn primarily from Leslie Cabarga, The Fleischer Story, (New York, 1988).

(5.) Max Fleischer was born in Austria in 1884, the family immigrated in 1887, and Dave was born in New York in 1894.

(6.) The nickelodeons played a variety of short subjects for a nickel. The earliest films were only a few minutes at most, but by 1905 films of a full reel (about 15 minutes) were being shown, and by 1910 multi reel narratives were becoming more common. For the location of the nickelodeons, see J. Hoberman, Bridge of Light: Yiddish Film Between Two Worlds, (Philadelphia, 1991), 26.

(7.) Noel Burch, Life to Those Shadows, trans, and ed., Ben Brewster (Berkeley: 1990),109.

(8.) Burch, Life, 112.

In the post-Code films Betty loses the ability to see ghosts and becomes a perfectly respectable young lady with a dog as a pet instead of as a boyfriend, impish nephews, and longer, less-revealing dresses. Soon her costars, like puppy Pudgy and crackpot inventor Grampy, take over as stars of the Fleischer cartoons, and Betty herself disappears by 1940. Mae Questel, Betty’s voice from 1931 to 1939, remarked that “Betty Boop ended when the studio moved to Florida [in 1938] and she was unable to move from New York.”(57) Questel was referring to herself, but she might as well have been talking about Betty. The Code had cut her off from her urban background five years earlier, and the move of the Fleischer studios merely confirmed that she was out of place in contemporary cinema.

Betty Boop was often compared to Mae West–another screen sexpot who lost her sting in post-Code Hollywood, but perhaps she should have been compared to the first sex-symbol of them all, Theda Bara, another good little Jewish girl who became a Hollywood star and an American fantasy.

(1.) Though I won’t discuss the Popeye cartoons here the early cartoons are also replete with Yiddish phrases and Jewish references.

(2.) Edison patented his peephole kinetoscope in January 1894. Film projection was invented in 1895, and by 1896 projected short films were being shown throughout the world.

(3.) Miriam Hansen, Babel & Babylon: Spectatorship in American Silent Film (Cambridge, 1991), 71.

(4.) Unless otherwise indicated, biographical information on the Fleischers is drawn primarily from Leslie Cabarga, The Fleischer Story, (New York, 1988).

(5.) Max Fleischer was born in Austria in 1884, the family immigrated in 1887, and Dave was born in New York in 1894.

(6.) The nickelodeons played a variety of short subjects for a nickel. The earliest films were only a few minutes at most, but by 1905 films of a full reel (about 15 minutes) were being shown, and by 1910 multi reel narratives were becoming more common. For the location of the nickelodeons, see J. Hoberman, Bridge of Light: Yiddish Film Between Two Worlds, (Philadelphia, 1991), 26.

(7.) Noel Burch, Life to Those Shadows, trans, and ed., Ben Brewster (Berkeley: 1990),109.

(8.) Burch, Life, 112.

(17.) Another of these city types is played by Koko the Clown, identified as the “man in the red tie.” Koko is clearly a gay character in this film, and the entire song, “Any Rags,” is full of 1920s homosexual slang (“Stick out your can, here comes the garbage man”). This is a cartoon firmly situated in its creators’ urban, theatrical milieu.

(18.) “Any Rags” (1931) and “Poor Cinderella” (1934) are two of many examples.

(19.) Burch, Life, 111-12.

(20.) Hansen, Babel, 61.

(21.) Hansen, p. 62.

(22.) Burch, p. 111.

(23.) Burch, p. 120

(24.) Hansen, p. 71.

(25.) Burch, note 1, p. 139.

(26.) Michael Rogin. Blackface, White Noise: Jewish Immigrants in the Hollywood Melting Pot. U. California Press; Berkeley, 1996. p. 42.

(27.) Most spectacularly, of course, in 1927’s The Jazz Singer, which also popularized sound film. For “soft racism,” See Burch, Life, 111.

(28.) Hoberman, p. 14.

(29.) The cinematographe, a combination camera, projector, and film developer, was invented in 1895 by the Lumiere brothers in Paris. Lumiere camera operators toured the world recording what they saw (actuality films) and presenting film shows. Outside of large city centers, the traveling Lumiere cameramen provided Europeans’ first encounter with cinema.

(30.) Hoberman, p. 14.

(31.) The first real Jewish movie mogul, Sigmund Lubin, began making films in 1907.

(32.) for an in-depth discussion of Jewish immigration patterns, see Irving Howe. World of Our Fathers.Schocken Books, Inc.; New York: 1989.

(33.) Hoberman, 36.

(34.) Hoberman, p. 17.

(35.) Hansen, p. 71.

(36.) Among other such features were A Child of the Ghetto (1910) and The Heart of a Jewess (1913); Hansen, p. 72-3.

(37.) Crafton, Donald. Before Mickey: The Animated Film 1898-1928. U. Chicago Press; Chicago: 1993. P. 11.

(38.) Before rotoscoping, animated drawings changed positions in jerky, disconnected movements. Audiences often found them difficult to watch. See Crafton, Before Mickey, or Cabarga, The Fleischer Story, for more on the development of animated cinema.

(39.) There are 16 frames per second in silent film, 24 in sound film. The first one-minute Koko cartoon contained 960 individually traced and inked frames.

(40.) See Cabarga, The Fleischer Story for the most complete description of the Fleischer innovations.

(41.) Crafton, p. 46. The film depicts an artist, Blackton, doing a faster-than-life sketch of Edison.

(42.) Crafton, p. 11.

(43.) Hoberman, p. 256.

(44.) Talkartoons soon became Betty Boop’s vehicle, but originally she was conceived of only as Bimbo’s dog-like girlfriend. Bimbo, Koko the Clown’s sidekick from the silent Out of the Inkwell series, was supposed to be the main attraction of the Talkartoons. Betty definitely looks more poodlelike in this cartoon than in her later guise. Cabarga, p. 53-7.

(45.) Rogin, p. 73-158.

(46.) Lenburg, Jeff. The Great Cartoon Directors. Da Capo Press; New York: 1993. p. 188.

(47.) Hoberman, p. 9.

(48.) The Marx Bros.’ comedy films are probably the best additional example. They also frequently include bits of Yiddish and have frequently been discussed as assimilationist fantasies (or nightmares). The famous stateroom scene from A Night at the Opera has been read by one student of mine (convincingly) as a parody of the conditions immigrants faced in steerage.

(49.) David Shneer, UC Berkeley Department of History. personal communication, 1999.

(50.) Sammond, Nic. “Imagineering the Normal Child: Disney and Development.”. UC Berkeley Film Conference; Berkeley: 1996. presentation.

(51.) Ibid.

(52.) Ibid.

(53.) In 1934 the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America, the official organization of the major and minor Hollywood studios, agreed to abide by the Production Code administered by the Hays Office. The provisions of the code forbid depictions of graphic violence, unpunished criminal behavior, graphic or immoral sexual relations (including depictions of homosexuality), profanity, miscegenation, and drug addiction. See David Cook. A History of Narrative Film. 3rd ed.. W.W. Norton & Co.; New York: 1996. pp. 282-3.

(54.) On the flipside of Betty’s ethnic suppleness is the constant appearance of other ethnic groups–African-Americans or, in this case, Samoans–in conjunction with Betty and Bimbo’s Jewish markers. While the real entertainers are visible in the films, introducing the animation with live-action musical segments of real black jazz or real Samoan dance, they then switch to incredibly broad animated caricatures of the same ethnics next to Betty and Bimbo in their normal guise, replicating the stereotypes direct from vaudeville.

(55.) Howard M. Sachar. A History of the Jews in America. Vintage Books; New York: 1993. pp. 300-04.

(56.) Hoberman, p. 54.

(57.) Cabarga, p. 113

Amelia S. Holberg completed her Ph.D.in Rhetoric at the University of California, Berkeley. Amelia S. Holberg is Assistant Professor of Media Studies at The Catholic University ofAmerica. Reprinted with permission from Lilith, the independent Jewish women’s magazine. To learn more about the magazine and to subscribe, visit www.Lilith.org or click here: Lilith Magazine

COPYRIGHT 1999 American Jewish Historical Society

COPYRIGHT 2008 Gale, Cengage Learning

Amelia S. Holberg “Betty Boop: Yiddish Film Star “. American Jewish History. FindArticles.com. 05 May, 2011. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_hb6389/is_4_87/ai_n28754698/

COPYRIGHT 1999 American Jewish Historical Society

COPYRIGHT 2008 Gale, Cengage Learning

Artículos Relacionados: